- Joined

- Feb 9, 2004

- Messages

- 17,078

Many people deny that Scripture teaches its own inerrancy, but Brian Edwards shows that, based on Scripture, Christians should absolutely hold to biblical inerrancy.

Introduction

“You don’t really believe the Bible is true, do you?”

The shock expressed by those who discover someone who actually believes the Bible to be without error is often quite amusing. Inevitably, their next question takes us right back to Genesis. But what does the Christian mean by “without error,” and why are we so sure?

Inspiring or Expiring?

Let’s start by understanding what we mean when we talk about the Bible as “inspired” because that word may mislead us. The term is an attempt to translate a word that occurs only once in the New Testament, and it’s not the best translation, even though William Tyndale introduced it back in 1526. The word is found in <cite class="bibleref">2 Timothy 3:16</cite>, and the Greek is theopneustos. This term is made from two words, one being the word for God (theos, as in theology) and the other referring to breath or wind (pneustos, as in pneumonia and pneumatic). It is significant that the word is used in <cite class="bibleref">2 Timothy 3:16</cite> passively. In other words, God did not “breathe into” (inspire) all Scripture, but it was “breathed out” by God (expired). Thus, <cite class="bibleref">2 Timothy 3:16</cite> is not about how the Bible came to us but where it came from. The Scriptures are “God-breathed.”

To know how the Bible came to us, we can turn to <cite class="bibleref">2 Peter 1:21</cite> where we discover that “holy men of God spoke as they were moved by the Holy Spirit.” The Greek word used here is pherō, which means “to bear” or “to carry.” It was a familiar word that Luke used of the sailing ship carried along by the wind (<cite class="bibleref">Acts 27:15, (17)</cite>). The human writers of the Bible certainly used their minds, but the Holy Spirit carried them along in their thinking so that only His God-breathed words were recorded. The Apostle Paul set the matter plainly in 1 Corinthians 2:13: “These things we also speak, not in words which man’s wisdom teaches but which the Holy Spirit teaches.”

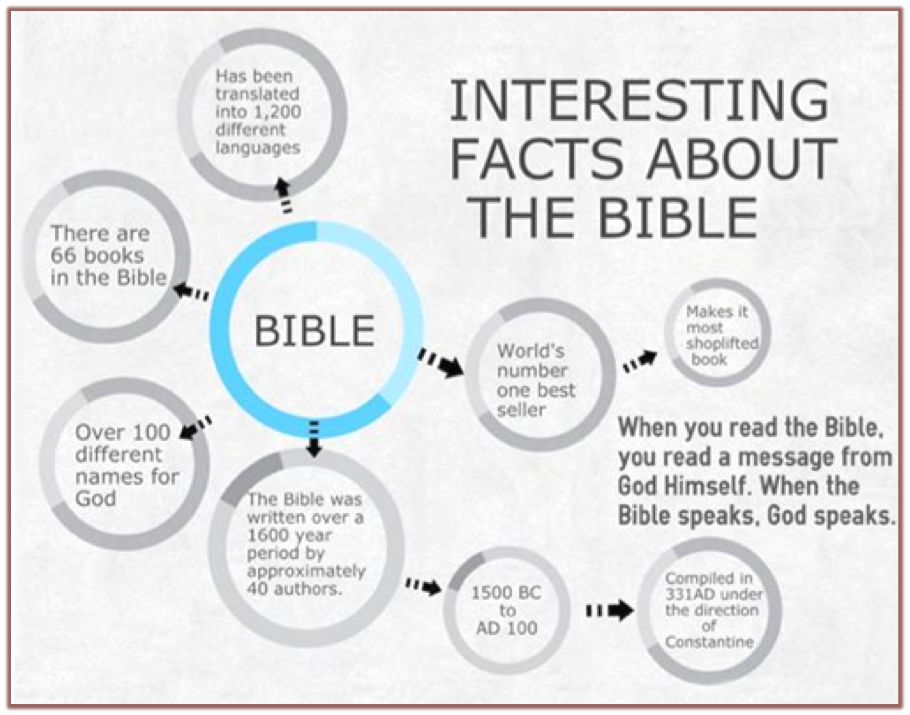

The word “inspiration” is so embedded in our Christian language that we will continue to use it, though we now know what it really means. God breathed out His Word, and the Holy Spirit guided the writers. The Bible has one Author and many (around 40) writers.

With these two acts of God—breathing out His Word and carrying the writers along by the Spirit—we can come to a definition of inspiration:

The Holy Spirit moved men to write. He allowed them to use their own styles, cultures, gifts, and character. He allowed them to use the results of their own study and research, write of their own experiences, and express what was in their minds. At the same time, the Holy Spirit did not allow error to influence their writings. He overruled in the expression of thought and in the choice of words. Thus, they recorded accurately all God wanted them to say and exactly how He wanted them to say it in their own character, styles, and languages.

The inspiration of Scripture is a harmony of the active mind of the writer and the sovereign direction of the Holy Spirit to produce God’s inerrant and infallible Word for the human race. Two errors are to be avoided here. First, some think inspiration is nothing more than a generally heightened sensitivity to wisdom on the part of the writer, just as we talk of an inspired idea or invention. Second, some believe the writer was merely a mechanical dictation machine, writing out the words he heard from God. Both errors fail to adequately account for the active role played by the Holy Spirit and the human writer.

How Much Is Inerrant?

If “inspired” really means “God-breathed,” then the claim of <cite class="bibleref">2 Timothy 3:16</cite> is that all Scripture, being God-breathed, is without error and therefore can be trusted completely. Since God cannot lie (<cite class="bibleref">Hebrews 6:18</cite>), He would cease to be God if He breathed out errors and contradictions, even in the smallest part. So long as we give theopneustos its real meaning, we shall not find it hard to understand the full inerrancy of the Bible.

Two words are sometimes used to explain the extent of biblical inerrancy: plenary and verbal. “Plenary” comes from the Latin plenus, which means “full,” and refers to the fact that the whole of Scripture in every part is God-given. “Verbal” comes from the Latin verbum, which means “word,” and emphasizes that even the words of Scripture are God-given. Plenary and verbal inspiration means the Bible is God-given (and therefore without error) in every part (doctrine, history, geography, dates, names) and in every single word.

When we talk about inerrancy, we refer to the original writings of Scripture. We do not have any of the original “autographs,” as they are called, but only copies, including many copies of each book. There are small differences here and there, but in reality they are amazingly similar. One eighteenth century New Testament scholar claimed that not one thousandth part of the text was affected by these differences. 1 Now that we know what inerrancy means, let’s cover what it doesn’t mean.

- Inerrancy doesn’t mean everything in the Bible is true. We have the record of men lying (e.g., <cite class="bibleref">Joshua 9</cite>) and even the words of the devil himself. But we can be sure these are accurate records of what took place.

- Inerrancy doesn’t mean apparent contradictions are not in the text, but these can be resolved. At times different words may be used in recounting what appears to be the same incident. For example, <cite class="bibleref">Matthew 3:11</cite> refers to John the Baptist carrying the sandals of the Messiah, whereas <cite class="bibleref">John 1:27</cite> refers to him untying them. John preached over a period of time, and he would repeat himself; like any preacher he would use different ways of expressing the same thing.

- Inerrancy doesn’t mean every extant copy is inerrant. It is important to understand that the doctrine of inerrancy only applies to the original manuscripts.

What Does the Bible Claim?

Is it true, as John Goldingay stated, that this view of inerrancy “is not directly asserted by Christ or within Scripture itself”? 3 Let’s look at what the Bible says about itself.

The View of the Old Testament Writers

The Old Testament writers saw their message as God-breathed and therefore utterly reliable. God promised Moses He would eventually send another prophet (Jesus Christ) who would also speak God’s words like Moses had done. “I will raise up for them a Prophet like you from among their brethren, and will put My words in His mouth, and He shall speak to them all that I command Him” (<cite class="bibleref">Deuteronomy 18:18</cite>). Jeremiah was told at the beginning of his ministry that he would speak for God. “Then the Lord put forth His hand and touched my mouth, and the Lord said to me: ‘Behold, I have put My words in your mouth’” (<cite class="bibleref">Jeremiah 1:9</cite>).

The Hebrew word for prophet means “a spokesman,” and the prophet’s message was on God’s behalf: “This is what the Lord says.” As a result they frequently so identified themselves with God that they spoke as though God Himself were actually speaking. <cite class="bibleref">Isaiah 5</cite> reveals this clearly. In verses 1–2 the prophet speaks of God in the third person (He), but in verses 3–6 Isaiah changes to speak in the first person (I). Isaiah was speaking the very words of God. No wonder King David could speak of the Word of the Lord as “flawless” (<cite class="bibleref">2 Samuel 22:31</cite>; see also <cite class="bibleref">Proverbs 30:5, (NIV)</cite>).

The New Testament Agrees with the Old Testament

Peter and John saw the words of David in <cite class="bibleref">Psalm 2</cite>, not merely as the opinion of a king of Israel, but as the voice of God. They introduced a quotation from that psalm in a prayer to God by saying, “who by the mouth of Your servant David have said: ‘Why did the nations rage, and the people plot vain things?’” (<cite class="bibleref">Acts 4:25</cite>).

Similarly, Paul accepted Isaiah’s words as God Himself speaking to men: “The Holy Spirit spoke rightly through Isaiah the prophet to our fathers” (<cite class="bibleref">Acts 28:25</cite>).

So convinced were the writers of the New Testament that all the words of the Old Testament Scripture were the actual words of God that they even claimed, “Scripture says,” when the words quoted came directly from God. Two examples are <cite class="bibleref">Romans 9:17</cite>, which states, “For the Scripture says to Pharaoh,” and <cite class="bibleref">Galatians 3:8</cite>, in which Paul wrote, “the Scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, preached the gospel to Abraham beforehand . . . .” In <cite class="bibleref">Hebrews 1</cite> many of the Old Testament passages quoted were actually addressed to God by the psalmist, yet the writer to the Hebrews refers to them as the words of God.

Jesus Believed in Verbal Inspiration

In <cite class="bibleref">John 10:34</cite> Jesus quoted from <cite class="bibleref">Psalm 82:6</cite> and based His teaching upon a phrase: “I said, ‘You are gods.’” In other words, Jesus proclaimed that the words of this psalm were the words of God. Similarly, in <cite class="bibleref">Matthew 22:31–32</cite> He claimed the words of Exodus 3:6 were given to them by God. In <cite class="bibleref">Matthew 22:43–44</cite> our Lord quoted from <cite class="bibleref">Psalm 110:1</cite> and pointed out that David wrote these words “in the Spirit,” meaning he was actually writing the words of God.

Paul Believed in Verbal Inspiration

Paul based an argument upon the fact that a particular word in the Old Testament is singular and not plural. Writing to the Galatians, Paul claimed that in God’s promises to Abraham, “He does not say, ‘And to seeds,’ as of many, but as of one, ‘And to your Seed,’ who is Christ” (<cite class="bibleref">Galatians 3:16</cite>). Paul quoted from <cite class="bibleref">Genesis 12:7; 13:15; and 24:7</cite>. In each of these verses, our translators used the word “descendants,” but the Hebrew word is singular. The same word is translated “seed” in <cite class="bibleref">Genesis 22:18</cite>. Paul’s argument here is that God was not primarily referring to Israel as the offspring of Abraham, but to Christ.

What is significant is the way Paul drew attention to the fact that the Hebrew word in Genesis is singular. This demonstrates a belief in verbal inspiration because it mattered to Paul whether God used a singular or plural in these passages of the Old Testament. It is therefore not surprising Paul wrote that one of the advantages of being a Jew was the fact that “they have been entrusted with the very words of God” (<cite class="bibleref">Romans 3:2, (NIV)</cite>). Even many critics of the Bible agree that the Scriptures clearly teach a doctrine of verbal inerrancy.

Self-authentication

To say the Bible is the Word of God and is therefore without error because the Bible itself makes this claim is seen by many as circular reasoning. It is rather like saying, “That prisoner must be innocent because he says he is.” Are we justified in appealing to the Bible’s own claim in settling this matter of its authority and inerrancy?

Actually, we use “self-authentication” every day. Whenever we say, “I think” or “I believe” or “I dreamed,” we are making a statement no one can verify. If people were reliable, witness to oneself would always be enough. In <cite class="bibleref">John 5:31–32</cite> Jesus said that self-witness is normally insufficient. Later, when Jesus claimed, “I am the light of the world” (<cite class="bibleref">John 8:12</cite>), the Pharisees attempted to correct Him by stating, “Here you are, appearing as your own witness; your testimony is not valid” (<cite class="bibleref">John 8:13, (NIV)</cite>). In defense, the Lord showed that in His case, because He is the Son of God, self-witness is reliable: “Even if I bear witness of Myself, My witness is true . . .” (<cite class="bibleref">John 8:14</cite>). Self-witness is reliable where sin does not interfere. Because Jesus is God and therefore guiltless (a fact confirmed by His critics in <cite class="bibleref">John 8:46</cite>), His words can be trusted. In a similar manner, since the Bible is God’s Word, we must listen to its own claims about itself.

Much of the Bible’s story is such that unless God had revealed it we could never have known it. Many scientific theories propose how the world came into being. Some of these theories differ only slightly from each other, but others are contradictory. This shows no one can really be sure about such matters because no scientist was there when it all happened. Unless the God who was there has revealed it, we could never know for certain. The same is true for all the great Bible doctrines. How can we be sure of God’s anger against sin, His love for sinners, or His plan to choose a people for Himself, unless God Himself has told us? Hilary of Poitiers, a fourth century theologian, once claimed, “Only God is a fit witness to himself”—and no one can improve upon that.

Who Believes This?

The belief the Bible is without error is not new. Clement of Rome in the first century wrote, “Look carefully into the Scriptures, which are the true utterances of the Holy Spirit. Observe that nothing of an unjust or counterfeit character is written in them.” 4 A century later, Irenaeus concluded, “The Scriptures are indeed perfect, since they were spoken by the Word of God and his Spirit.” 5

This was the view of the early church leaders, and it has been the consistent view of evangelicals from the ancient Vaudois people of the Piedmont Valley to the sixteenth century Protestant Reformers across Europe and up to the present day. Not all used the terms “infallibility” or “inerrancy,” but many expressed the concepts, and there is no doubt they believed it. It is liberalism that has taken a new approach. Professor Kirsopp Lake at Harvard University admitted, “It is we [the liberals] who have departed from the tradition.” 6

Does It Matter?

Is the debate about whether or not the Bible can be trusted merely a theological quibble? Certainly not! The question of ultimate authority is of tremendous importance for the Christian.

Inerrancy Governs Our Confidence in the Truth of the Gospel

If the Scripture is unreliable, can we offer the world a reliable gospel? How can we be sure of truth on any issue if we are suspicious of errors anywhere in the Bible? A pilot will ground his aircraft even on suspicion of the most minor fault, because he is aware that one fault destroys confidence in the complete machine. If the history contained in the Bible is wrong, how can we be sure the doctrine or moral teaching is correct?

The heart of the Christian message is history. The Incarnation (God becoming a man) was demonstrated by the Virgin Birth of Christ. Redemption (the price paid for our rebellion) was obtained by the death of Christ on the Cross. Reconciliation (the privilege of the sinner becoming a friend of God) was gained through the Resurrection and Ascension of Christ. If these recorded events are not true, how do we know the theology behind them is true?

Inerrancy Governs Our Faith in the Value of Christ

We cannot have a reliable Savior without a reliable Scripture. If, as many suggest, the stories in the Gospels are not historically true and the recorded words of Christ are only occasionally His, how do we know what we can trust about Christ? Must we rely upon the conflicting interpretations of a host of critical scholars before we know what Christ was like or what He taught? If the Gospel stories are merely the result of the wishful thinking of the church in the second or third centuries, or even the personal views of the Gospel writers, then our faith no longer rests upon Jesus but upon the opinions of men. Who would trust an unreliable Savior for their eternal salvation?

Inerrancy Governs Our Response to the Conclusions of Science

If we believe the Bible contains errors, then we will be quick to accept scientific theories that appear to prove the Bible wrong. In other words, we will allow the conclusions of science to dictate the accuracy of the Word of God. When we doubt the Bible’s inerrancy, we have to invent new principles for interpreting Scripture that for convenience turn history into poetry and facts into myths. This means people must ask how reliable a given passage is when they turn to it. Only then will they be able to decide what to make of it. On the other hand, if we believe in inerrancy, we will test by Scripture the hasty theories that often come to us in the name of science.

Inerrancy Governs Our Attitude to the Preaching of Scripture

A denial of biblical inerrancy always leads to a loss of confidence in Scripture both in the pulpit and in the pew. It was not the growth of education and science that emptied churches, nor was it the result of two world wars. Instead, it was the cold deadness of theological liberalism. If the Bible’s history is doubtful and its words are open to dispute, then people understandably lose confidence in it. People want authority. They want to know what God has said.

Inerrancy Governs Our Belief in the Trustworthy Character of God

Almost all theologians agree Scripture is in some measure God’s revelation to the human race. But to allow that it contains error implies God has mishandled inspiration and has allowed His people to be deceived for centuries until modern scholars disentangled the confusion. In short, the Maker muddled the instructions.

Conclusion

A church without the authority of Scripture is like a crocodile without teeth; it can open its mouth as wide and as often as it likes—but who cares? Thankfully, God has given us His inspired, inerrant, and infallible Word. His people can speak with authority and boldness, and we can be confident we have His instructions for our lives.

Footnotes

- Bishop Brook Foss Westcott, The New Testament in the Original Greek (London, MacMillan, 1881), 2.

- John Goldingay, Models for Scripture (Toronto: Clements Publishing, 2004), 282.

- Ibid.

- Clement of Rome First letter to the Corinthians XLV.

- Irenaeus, Against Heresies, XVII.2.

- Kirsopp Lake, The Religion of Yesterday and Tomorrow, (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin Co., 1926), 62.